- Home

- Brand

- Distortions (45)

- Gemmy (398)

- Halloween (18)

- Handmade (30)

- Haunted Hill Farm (19)

- Home Accents Holiday (138)

- Magic Power (14)

- Morbid Enterprises (28)

- Morris (51)

- Morris Costumes (100)

- Neca (12)

- Seasonal Visions (146)

- Skeleton Store (13)

- Spirit (45)

- Spirit Halloween (184)

- Tekky (15)

- Tekky Toys (24)

- Trick Or Treat (16)

- Www.horror-hall.com (24)

- Xcoser (85)

- ... (4397)

- Material

- Occasion

- Power Type

- Shipping Policy

- Type

- Action Figure (8)

- Animated Prop (5)

- Animatronic (26)

- Cosplay Helmet (6)

- Cosplay Mask Helmet (8)

- Doll (9)

- Halloween (26)

- Halloween Decor (7)

- Halloween Prop (9)

- Helmet (5)

- Mask (5)

- Prop (25)

- Props (8)

- Puppet (6)

- Replica Weapons (4)

- Seasonal Props (7)

- Skeleton (6)

- Statue (7)

- Undefined (4)

- Yard Decor (5)

- ... (5616)

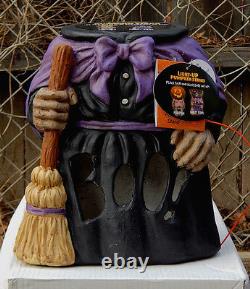

12 LIGHT UP PLASTER WITCH PUMPKIN STAND rare Halloween prop bowl stand garden

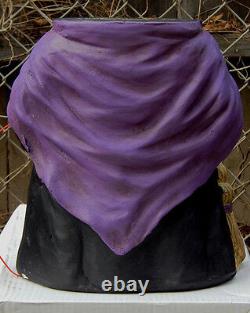

Check out our other new & used items>>>>> HERE! A limited-run, now retired decorative piece from the 2016 Halloween season. 12 LIGHT-UP WITCH PUMPKIN/CANDY BOWL STAND BY SPOOKY VILLAGE. Put your jack-o'-lantern on a pedestal with a fantastically unique pumpkin stand! Stand measures approximately 12 inches in height and is the perfect place to show off your carved pumpkin design or easily distribute treats by placing a candy bowl on top.

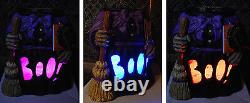

The pumpkin/candy bowl stand resembles an old, headless wicked witch complete with black full-cover dress and broom. Because most of the stand is black the BOO!

Cut-out looks more pronounced and eerie when lit and seen after sundown. When activated, either by the "Try Me" button or "On/Off" switch, this decorative piece will light inside making the hollow space in-between the skeleton's ribs glow a radiant, demon-red. The "Try Me" button activates the red light and stays on for as long as you keep the button pressed. The "On/Off" switch will activate the light, which will stay on until the switch is set back to the "Off" position. Made of plaster and hand-painted!This awesome Halloween time home decoration is constructed of plaster, has some real weight to it and is hand-painted. The designer/sculptor of the original mold and overall look did a wonderful job including detail, on the broom and witch's hands. Because this pumpkin stand is made of plaster its paint can easily be touched-up, enhanced or a whole new paint scheme can be applied. Ideal for displaying during the Halloween season though lovers of all things macabre can enjoy it all-year-round as it sits upon a shelf or in a corner in their decorated home of horrors.

Uses 3 "AAA" batteries to operate light. Original demo batteries are included - may need replacing upon receiving pumpkin stand. Approximately 12"(H) x 10 7/8"(W) x 6 5/8(D). The pumpkin stand weighs approximately 5.7 pounds. New with tags and some shelf wear.

Though the pumpkin stand has an intentional distressed/weathered look it also has a few small, unintentional missing specks of paint and plaster (can easily be touched up with some craftiness). There is an intentional, small hole by the bow where the tags hang from. For photo purposes and to test for working order the light was turned on for a short period of time. ALL PHOTOS AND TEXT ARE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OF SIDEWAYS STAIRS CO. Halloween or Hallowe'en (a contraction of Hallows' Even or Hallows' Evening), [5] also known as Allhalloween, [6] All Hallows' Eve, [7] or All Saints' Eve, [8] is a celebration observed in several countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day. It begins the three-day observance of Allhallowtide, [9] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed. It is widely believed that many Halloween traditions originated from ancient Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain; that such festivals may have had pagan roots; and that Samhain itself was Christianized as Halloween by the early Church. [12][13][14][15][16] Some believe, however, that Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, separate from ancient festivals like Samhain.Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising and souling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins into jack-o'-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, as well as watching horror films. [21] In many parts of the world, the Christian religious observances of All Hallows' Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead, remain popular, [22][23][24] although elsewhere it is a more commercial and secular celebration. [25][26][27] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows' Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes...

The word Halloween or Hallowe'en dates to about 1745[32] and is of Christian origin. [33] The word "Hallowe'en" means "Saints' evening". [34] It comes from a Scottish term for All Hallows' Eve (the evening before All Hallows' Day). [35] In Scots, the word "eve" is even, and this is contracted to e'en or een. Over time, (All) Hallow(s) E(v)en evolved into Hallowe'en.

Although the phrase "All Hallows'" is found in Old English "All Hallows' Eve" is itself not seen until 1556.... Lesley Bannatyne and Cindy Ott both write that Anglican colonists in the Southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland "recognized All Hallow's Eve in their church calendars", [117][118] although the Puritans of New England maintained strong opposition to the holiday, along with other traditional celebrations of the established Church, including Christmas. [119] Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century give no indication that Halloween was widely celebrated in North America. [120] It was not until mass Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century that Halloween became a major holiday in North America.

[120] Confined to the immigrant communities during the mid-19th century, it was gradually assimilated into mainstream society and by the first decade of the 20th century it was being celebrated coast to coast by people of all social, racial and religious backgrounds. [121] In Cajun areas, a nocturnal Mass was said in cemeteries on Halloween night. Candles that had been blessed were placed on graves, and families sometimes spent the entire night at the graveside. [122] The yearly New York Halloween Parade, begun in 1974 by puppeteer and mask maker Ralph Lee of Greenwich Village, is the world's largest Halloween parade and one of America's only major nighttime parades (along with Portland's Starlight Parade), attracting more than 60,000 costumed participants, two million spectators, and a worldwide television audience of over 100 million...

Development of artifacts and symbols associated with Halloween formed over time. Jack-o'-lanterns are traditionally carried by guisers on All Hallows' Eve in order to frighten evil spirits. [99][124] There is a popular Irish Christian folktale associated with the jack-o'-lantern, [125] which in folklore is said to represent a "soul who has been denied entry into both heaven and hell":[126].

On route home after a night's drinking, Jack encounters the Devil and tricks him into climbing a tree. A quick-thinking Jack etches the sign of the cross into the bark, thus trapping the Devil. Jack strikes a bargain that Satan can never claim his soul. After a life of sin, drink, and mendacity, Jack is refused entry to heaven when he dies. Keeping his promise, the Devil refuses to let Jack into hell and throws a live coal straight from the fires of hell at him.

It was a cold night, so Jack places the coal in a hollowed out turnip to stop it from going out, since which time Jack and his lantern have been roaming looking for a place to rest. In Ireland and Scotland, the turnip has traditionally been carved during Halloween, [128][129] but immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin, which is both much softer and much larger making it easier to carve than a turnip. [128] The American tradition of carving pumpkins is recorded in 1837[130] and was originally associated with harvest time in general, not becoming specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late 19th century. [132][133] Imagery of the skull, a reference to Golgotha in the Christian tradition, serves as "a reminder of death and the transitory quality of human life" and is consequently found in memento mori and vanitas compositions;[134] skulls have therefore been commonplace in Halloween, which touches on this theme. [135] Traditionally, the back walls of churches are "decorated with a depiction of the Last Judgment, complete with graves opening and the dead rising, with a heaven filled with angels and a hell filled with devils", a motif that has permeated the observance of this triduum.

[136] One of the earliest works on the subject of Halloween is from Scottish poet John Mayne, who, in 1780, made note of pranks at Halloween; What fearfu' pranks ensue! ", as well as the supernatural associated with the night, "Bogies" (ghosts), influencing Robert Burns' "Halloween (1785).

[137] Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent. Homes are often decorated with these types of symbols around Halloween. Halloween imagery includes themes of death, evil, and mythical monsters. [138] Black, orange, and sometimes purple are Halloween's traditional colors... Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween.

" The word "trick" implies a "threat to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given. [86] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling. [139] John Pymm writes that many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church. [140] These feast days included All Hallows' Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday.

[141][142] Mumming practiced in Germany, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, [143] involved masked persons in fancy dress who "paraded the streets and entered houses to dance or play dice in silence". [88] In the Philippines, the practice of souling is called Pangangaluwa and is practiced on All Hallow's Eve among children in rural areas.

[21] People drape themselves in white cloths to represent souls and then visit houses, where they sing in return for prayers and sweets. [129][147] The practice of guising at Halloween in North America is first recorded in 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, Canada reported children going "guising" around the neighborhood.American historian and author Ruth Edna Kelley of Massachusetts wrote the first book-length history of Halloween in the US; The Book of Hallowe'en (1919), and references souling in the chapter "Hallowe'en in America". While the first reference to "guising" in North America occurs in 1911, another reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920.

[151] The earliest known use in print of the term "trick or treat" appears in 1927, in the Blackie Herald Alberta, Canada. The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show children but not trick-or-treating. [153] Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice until the 1930s, with the first US appearances of the term in 1934, [154] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.

A popular variant of trick-or-treating, known as trunk-or-treating (or Halloween tailgaiting), occurs when "children are offered treats from the trunks of cars parked in a church parking lot", or sometimes, a school parking lot. [116][156] In a trunk-or-treat event, the trunk (boot) of each automobile is decorated with a certain theme, [157] such as those of children's literature, movies, scripture, and job roles. [158] Trunk-or-treating has grown in popularity due to its perception as being more safe than going door to door, a point that resonates well with parents, as well as the fact that it "solves the rural conundrum in which homes [are] built a half-mile apart"... There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween.

Some of these games originated as divination rituals or ways of foretelling one's future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a "rare few" in rural communities as they were considered to be "deadly serious" practices. [167] In recent centuries, these divination games have been "a common feature of the household festivities" in Ireland and Britain.

[58] They often involve apples and hazelnuts. In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom. [168] Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona. The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th20th centuries.

Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today. One common game is apple bobbing or dunking (which may be called "dooking" in Scotland)[169] in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water and the participants must use only their teeth to remove an apple from the basin. A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drive the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a sticky face. Another once-popular game involves hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other.

The rod is spun round and everyone takes turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth. Several of the traditional activities from Ireland and Britain involve foretelling one's future partner or spouse. An apple would be peeled in one long strip, then the peel tossed over the shoulder. The peel is believed to land in the shape of the first letter of the future spouse's name. [171][172] Two hazelnuts would be roasted near a fire; one named for the person roasting them and the other for the person they desire.

If the nuts jump away from the heat, it is a bad sign, but if the nuts roast quietly it foretells a good match. [173][174] A salty oatmeal bannock would be baked; the person would eat it in three bites and then go to bed in silence without anything to drink. This is said to result in a dream in which their future spouse offers them a drink to quench their thirst. [175] Unmarried women were told that if they sat in a darkened room and gazed into a mirror on Halloween night, the face of their future husband would appear in the mirror.

[176] However, if they were destined to die before marriage, a skull would appear. The custom was widespread enough to be commemorated on greeting cards[177] from the late 19th century and early 20th century.

In Ireland and Scotland, items would be hidden in food usually a cake, barmbrack, cranachan, champ or colcannon and portions of it served out at random. A person's future would be foretold by the item they happened to find; for example, a ring meant marriage and a coin meant wealth. Up until the 19th century, the Halloween bonfires were also used for divination in parts of Scotland, Wales and Brittany.

When the fire died down, a ring of stones would be laid in the ashes, one for each person. In the morning, if any stone was mislaid it was said that the person it represented would not live out the year. Telling ghost stories and watching horror films are common fixtures of Halloween parties.Episodes of television series and Halloween-themed specials (with the specials usually aimed at children) are commonly aired on or before Halloween, while new horror films are often released before Halloween to take advantage of the holiday... Haunted attractions are entertainment venues designed to thrill and scare patrons. Most attractions are seasonal Halloween businesses that may include haunted houses, corn mazes, and hayrides, [179] and the level of sophistication of the effects has risen as the industry has grown. The first recorded purpose-built haunted attraction was the Orton and Spooner Ghost House, which opened in 1915 in Liphook, England.

This attraction actually most closely resembles a carnival fun house, powered by steam. [180][181] The House still exists, in the Hollycombe Steam Collection. It was during the 1930s, about the same time as trick-or-treating, that Halloween-themed haunted houses first began to appear in America. It was in the late 1950s that haunted houses as a major attraction began to appear, focusing first on California. Sponsored by the Children's Health Home Junior Auxiliary, the San Mateo Haunted House opened in 1957.The San Bernardino Assistance League Haunted House opened in 1958. Home haunts began appearing across the country during 1962 and 1963. In 1964, the San Manteo Haunted House opened, as well as the Children's Museum Haunted House in Indianapolis. The haunted house as an American cultural icon can be attributed to the opening of the Haunted Mansion in Disneyland on 12 August 1969. [183] Knott's Berry Farm began hosting its own Halloween night attraction, Knott's Scary Farm, which opened in 1973.

[184] Evangelical Christians adopted a form of these attractions by opening one of the first "hell houses" in 1972. The first Halloween haunted house run by a nonprofit organization was produced in 1970 by the Sycamore-Deer Park Jaycees in Clifton, Ohio. It was last produced in 1982. [186] Other Jaycees followed suit with their own versions after the success of the Ohio house. The March of Dimes copyrighted a "Mini haunted house for the March of Dimes" in 1976 and began fundraising through their local chapters by conducting haunted houses soon after.

Although they apparently quit supporting this type of event nationally sometime in the 1980s, some March of Dimes haunted houses have persisted until today. On the evening of 11 May 1984, in Jackson Township, New Jersey, the Haunted Castle (Six Flags Great Adventure) caught fire. As a result of the fire, eight teenagers perished. [188] The backlash to the tragedy was a tightening of regulations relating to safety, building codes and the frequency of inspections of attractions nationwide. The smaller venues, especially the nonprofit attractions, were unable to compete financially, and the better funded commercial enterprises filled the vacuum. [189][190] Facilities that were once able to avoid regulation because they were considered to be temporary installations now had to adhere to the stricter codes required of permanent attractions. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, theme parks entered the business seriously.Six Flags Fright Fest began in 1986 and Universal Studios Florida began Halloween Horror Nights in 1991. Knott's Scary Farm experienced a surge in attendance in the 1990s as a result of America's obsession with Halloween as a cultural event. Theme parks have played a major role in globalizing the holiday.

Universal Studios Singapore and Universal Studios Japan both participate, while Disney now mounts Mickey's Not-So-Scary Halloween Party events at its parks in Paris, Hong Kong and Tokyo, as well as in the United States. [194] The theme park haunts are by far the largest, both in scale and attendance. Witchcraft (or witchery) is the practice of magical skills and abilities. Witchcraft is a broad term that varies culturally and societally, and thus can be difficult to define with precision, [1] therefore cross-cultural assumptions about the meaning or significance of the term should be applied with caution. Historically, and in most traditional cultures worldwide - notably in Africa and in traditional Native American communities - the term is commonly associated with those who use metaphysical means to cause harm to the innocent.[2][3][4][5] In the modern era, especially among younger, urban and white peoples in America and Europe, the word may more commonly refer to benign or positive practices of modern paganism, [6][7] where it may refer to a divinatory or healing role. Belief in witchcraft is often present within societies and groups whose cultural framework includes a magical world view... The concept of witchcraft and the belief in its existence have persisted throughout recorded history. They have been present or central at various times and in many diverse forms among cultures and religions worldwide, including both "primitive" and "highly advanced" cultures, [9] and continue to have an important role in many cultures today. Historically, the predominant concept of witchcraft in the Western world derives from Old Testament laws against witchcraft, and entered the mainstream when belief in witchcraft gained Church approval in the Early Modern Period.

It posits a theosophical conflict between good and evil, where witchcraft was generally evil and often associated with the Devil and Devil worship. This culminated in deaths, torture and scapegoating (casting blame for human misfortune), [10][11] and many years of large scale witch-trials and witch hunts, especially in Protestant Europe, before largely ceasing during the European Age of Enlightenment.

Christian views in the modern day are diverse and cover the gamut of views from intense belief and opposition (especially by Christian fundamentalists) to non-belief, and even approval in some churches. From the mid-20th century, witchcraft sometimes called contemporary witchcraft to clearly distinguish it from older beliefs became the name of a branch of modern paganism.

It is most notably practiced in the Wiccan and modern witchcraft traditions, and it is no longer practiced in secrecy. The Western mainstream Christian view is far from the only societal perspective about witchcraft. Many cultures worldwide continue to have widespread practices and cultural beliefs that are loosely translated into English as "witchcraft", although the English translation masks a very great diversity in their forms, magical beliefs, practices, and place in their societies. During the Age of Colonialism, many cultures across the globe were exposed to the modern Western world via colonialism, usually accompanied and often preceded by intensive Christian missionary activity (see "Christianization"). In these cultures beliefs that were related to witchcraft and magic were influenced by the prevailing Western concepts of the time.

Witch-hunts, scapegoating, and the killing or shunning of suspected witches still occur in the modern era. Suspicion of modern medicine due to beliefs about illness being due to witchcraft also continues in many countries to this day, with tragic healthcare consequences.HIV/AIDS[5] and Ebola virus disease[14] are two examples of often-lethal infectious disease epidemics whose medical care and containment has been severely hampered by regional beliefs in witchcraft. Other severe medical conditions whose treatment is hampered in this way include tuberculosis, leprosy, epilepsy and the common severe bacterial Buruli ulcer...

The word witch is of uncertain origin. There are numerous etymologies that it could be derived from. One popular belief is that it is "related to the English words wit, wise, wisdom [Germanic root weit-, wait-, wit-; Indo-European root weid-, woid-, wid-], " so craft of the wise. "[17] Another is from the Old English wiccecræft, a compound of "wicce" ("witch") and "cræft" ("craft). In anthropological terminology, witches differ from sorcerers in that they don't use physical tools or actions to curse; their maleficium is perceived as extending from some intangible inner quality, and one may be unaware of being a witch, or may have been convinced of his/her nature by the suggestion of others.

[19] This definition was pioneered in a study of central African magical beliefs by E. Evans-Pritchard, who cautioned that it might not correspond with normal English usage. Historians of European witchcraft have found the anthropological definition difficult to apply to European witchcraft, where witches could equally use (or be accused of using) physical techniques, as well as some who really had attempted to cause harm by thought alone. [2] European witchcraft is seen by historians and anthropologists as an ideology for explaining misfortune; however, this ideology has manifested in diverse ways, as described below... Professor Norman Gevitz wrote, that. It is argued here that the medical arts played a significant and sometimes pivotal role in the witchcraft controversies of seventeenth-century New England. Not only were physicians and surgeons the principal professional arbiters for determining natural versus preternatural signs and symptoms of disease, they occupied key legislative, judicial, and ministerial roles relating to witchcraft proceedings. Forty six male physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries are named in court transcripts or other contemporary source materials relating to New England witchcraft. These practitioners served on coroners' inquests, performed autopsies, took testimony, issued writs, wrote letters, or committed people to prison, in addition to diagnosing and treating patients. Some practitioners are simply mentioned in passing. Where belief in malicious magic practices exists, such practitioners are typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while beneficial magic is tolerated or even accepted wholesale by the people even if the orthodox establishment opposes it. Probably the most widely known characteristic of a witch was the ability to cast a spell, "spell" being the word used to signify the means employed to carry out a magical action. A spell could consist of a set of words, a formula or verse, or a ritual action, or any combination of these. [24] Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of runes or sigils on an object to give it magical powers; by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (poppet) of a person to affect him or her magically; by the recitation of incantations; by the performance of physical rituals; by the employment of magical herbs as amulets or potions; by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (scrying) for purposes of divination; and by many other means.Necromancy (conjuring the dead)[edit]. Strictly speaking, "necromancy" is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for divination or prophecy although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical Witch of Endor performed it 1 Sam.

28, and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham:[26][27][28] Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arise from death. In Christianity and Islam, sorcery came to be associated with heresy and apostasy and to be viewed as evil. Among the Catholics, Protestants, and secular leadership of the European Late Medieval/Early Modern period, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts. The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft, culminating in the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena. [30] Throughout this time, it was increasingly believed that Christianity was engaged in an apocalyptic battle against the Devil and his secret army of witches, who had entered into a diabolical pact.

In total, tens or hundreds of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men. [31][32] In early modern Scots, the word Warlock came to be used as the male equivalent of witch (which can be male or female, but is used predominantly for females). The Malleus Maleficarum, (Latin for "Hammer of The Witches") was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants[34] for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on the work. Further information: Folk religion, Magical thinking, and Shamanism. Throughout the early modern period, the English term "witch" was not exclusively negative in meaning, and could also indicate cunning folk.As Alan McFarlane noted, There were a number of interchangeable terms for these practitioners,'white','good', or'unbinding' witches, blessers, wizards, sorcerers, however'cunning-man' and'wise-man' were the most frequent. "[36] The contemporary Reginald Scot explained, "At this day it is indifferent to say in the English tongue,'she is a witch' or'she is a wise woman'.

[37] Folk magicians throughout Europe were often viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing, [3] which could lead to their being accused as "witches" in the negative sense. Many English "witches" convicted of consorting with demons seem to have been cunning folk whose fairy familiars had been demonised;[38] many French devins-guerisseurs ("diviner-healers") were accused of witchcraft, [39] and over one half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers. Some of the healers and diviners historically accused of witchcraft have considered themselves mediators between the mundane and spiritual worlds, roughly equivalent to shamans. [41] Such people described their contacts with fairies, spirits often involving out-of-body experiences and travelling through the realms of an "other-world"... Witches have a long history of being depicted in art, although most of their earliest artistic depictions seem to originate in Early Modern Europe, particularly the Medieval and Renaissance periods. Many scholars attribute their manifestation in art as inspired by texts such as Canon Episcopi, a demonology-centered work of literature, and Malleus Maleficarum, a "witch-craze" manual published in 1487, by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. Canon Episcopi, a ninth-century text that explored the subject of demonology, initially introduced concepts that would continuously be associated with witches, such as their ability to fly or their believed fornication and sexual relations with the devil. The text refers to two women, Diana the Huntress and Herodias, who both express the duality of female sorcerers.Diana was described as having a heavenly body and as the "protectress of childbirth and fertility" while Herodias symbolized "unbridled sensuality". They thus represent the mental powers and cunning sexuality that witches used as weapons to trick men into performing sinful acts which would result in their eternal punishment. These characteristics were distinguished as Medusa-like or Lamia-like traits when seen in any artwork (Medusa's mental trickery was associated with Diana the Huntress's psychic powers and Lamia was a rumored female figure in the Medieval ages sometimes used in place of Herodias). One of the first individuals to regularly depict witches after the witch-craze of the medieval period was Albrecht Dürer, a German Renaissance artist. His famous 1497 engraving The Four Witches, portrays four physically attractive and seductive nude witches.

Their supernatural identities are emphasized by the skulls and bones lying at their feet as well as the devil discreetly peering at them from their left. The women's sensuous presentation speaks to the overtly sexual nature they were attached to in early modern Europe. Moreover, this attractiveness was perceived as a danger to ordinary men who they could seduce and tempt into their sinful world. [205] Some scholars interpret this piece as utilizing the logic of the Canon Episcopi, in which women used their mental powers and bodily seduction to enslave and lead men onto a path of eternal damnation, differing from the unattractive depiction of witches that would follow in later Renaissance years.

Dürer also employed other ideas from the Middle Ages that were commonly associated with witches. Specifically, his art often referred to former 12th- to 13th-century Medieval iconography addressing the nature of female sorcerers. In the Medieval period, there was a widespread fear of witches, accordingly producing an association of dark, intimidating characteristics with witches, such as cannibalism (witches described as "[sucking] the blood of newborn infants"[205]) or described as having the ability to fly, usually on the back of black goats. As the Renaissance period began, these concepts of witchcraft were suppressed, leading to a drastic change in the sorceress' appearances, from sexually explicit beings to the'ordinary' typical housewives of this time period. This depiction, known as the'Waldensian' witch became a cultural phenomenon of early Renaissance art.The term originates from the 12th-century monk Peter Waldo, who established his own religious sect which explicitly opposed the luxury and commodity-influenced lifestyle of the Christian church clergy, and whose sect was excommunicated before being persecuted as "practitioners of witchcraft and magic". Subsequent artwork exhibiting witches tended to consistently rely on cultural stereotypes about these women.

These stereotypes were usually rooted in early Renaissance religious discourse, specifically the Christian belief that an "earthly alliance" had taken place between Satan's female minions who "conspired to destroy Christendom". Another significant artist whose art consistently depicted witches was Dürer's apprentice, Hans Baldung Grien, a 15th-century German artist. His chiaroscuro woodcut, Witches, created in 1510, visually encompassed all the characteristics that were regularly assigned to witches during the Renaissance. Social beliefs labeled witches as supernatural beings capable of doing great harm, possessing the ability to fly, and as cannibalistic. [252] The urn in Witches seems to contain pieces of the human body, which the witches are seen consuming as a source of energy. Meanwhile, their nudity while feasting is recognized as an allusion to their sexual appetite, and some scholars read the witch riding on the back of a goat-demon as representative of their "flight-inducing [powers]". This connection between women's sexual nature and sins was thematic in the pieces of many Renaissance artists, especially Christian artists, due to cultural beliefs which characterized women as overtly sexual beings who were less capable (in comparison to men) of resisting sinful temptation. Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. [1] In English "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "render" commonly refers to external applications. [2] Another imprecise term used for the material is stucco, which is also often used for plasterwork that is worked in some way to produce relief decoration, rather than flat surfaces. The most common types of plaster mainly contain either gypsum, lime, or cement, [3] but all work in a similar way. The plaster is manufactured as a dry powder and is mixed with water to form a stiff but workable paste immediately before it is applied to the surface.The reaction with water liberates heat through crystallization and the hydrated plaster then hardens. Plaster can be relatively easily worked with metal tools or even sandpaper, and can be moulded, either on site or to make pre-formed sections in advance, which are put in place with adhesive.

Plaster is not a strong material; it is suitable for finishing, rather than load-bearing, and when thickly applied for decoration may require a hidden supporting framework, usually in metal. Forms of plaster have several other uses. In medicine plaster orthopedic casts are still often used for supporting set broken bones. In dentistry plaster is used to make dental impressions. Various types of models and moulds are made with plaster. In art, lime plaster is the traditional matrix for fresco painting; the pigments are applied to a thin wet top layer of plaster and fuse with it so that the painting is actually in coloured plaster. In the ancient world, as well as the sort of ornamental designs in plaster relief that are still used, plaster was also widely used to create large figurative reliefs for walls, though few of these have survived... Clay plaster is a mixture of clay, sand and water with the addition of plant fibers for tensile strength over wood lath. Clay plaster has been used since antiquity.Settlers in the American colonies used clay plaster on the interiors of their houses: Interior plastering in the form of clay antedated even the building of houses of frame, and must have been visible in the inside of wattle filling in those earliest frame houses in which wainscot had not been indulged. Clay continued in the use long after the adoption of laths and brick filling for the frame.

[4] Where lime was not available or easily accessible it was rationed or substituted with other binders. Weavers seminal work he says, Mud plaster consists of clay or earth which is mixed with water to give a plastic or workable consistency. If the clay mixture is too plastic it will shrink, crack and distort on drying. It will also probably drop off the wall. Sand and fine gravels were added to reduce the concentrations of fine clay particles which were the cause of the excessive shrinkage.

[5] Straw or grass was added sometimes with the addition of manure. In the Earliest European settlers plasterwork, a mud plaster was used or more usually a mud-lime mixture. [6] McKee [4] writes, of a circa 1675 Massachusetts contract that specified the plasterer, Is to lath and siele[7] the four rooms of the house betwixt the joists overhead with a coat of lime and haire upon the clay; also to fill the gable ends of the house with ricks and plaister them with clay. To lath and plaster partitions of the house with clay and lime, and to fill, lath, and plaister them with lime and haire besides; and to siele and lath them overhead with lime; also to fill, lath, and plaster the kitchen up to the wall plate on every side. The said Daniel Andrews is to find lime, bricks, clay, stone, haire, together with laborers and workmen. [8] Records of the New Haven colony in 1641 mention clay and hay as well as lime and hair also. In German houses of Pennsylvania the use of clay persisted.Old Economy Village is one such German settlement. The early Nineteenth-Century utopian village in present-day Ambridge, Pennsylvania, used clay plaster substrate exclusively in the brick and wood frame high architecture of the Feast Hall, Great House and other large and commercial structures as well as in the brick, frame and log dwellings of the society members. The use of clay in plaster and in laying brickwork appears to have been a common practice at that time not just in the construction of Economy village when the settlement was founded in 1824. Specifications for the construction of, Lock keepers houses on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, written about 1828, require stone walls to be laid with clay mortar, excepting 3 inches on the outside of the wallswhich (are) to be good lime mortar and well pointed. [10] The choice of clay was because of its low cost, but also the availability.

At Economy, root cellars dug under the houses yielded clay and sand (stone), or the nearby Ohio river yielded washed sand from the sand bars; and lime outcroppings and oyster shell for the lime kiln. Other required building materials were also sourced locally.

The surrounding forests of the new village of Economy provided straight grain, old-growth oak trees for lath. [11] Hand split lath starts with a log of straight grained wood of the required length. The log is spit into quarters and then smaller and smaller bolts with wedges and a sledge. When small enough, a froe and mallet were used to split away narrow strips of lath - unattainable with field trees and their many limbs.

Farm animals pastured in the fields cleared of trees provided the hair and manure for the float coat of plaster. Fields of wheat and grains provided straw and other grasses for binders for the clay plaster. But there was no uniformity in clay plaster recipes.

Straw or grass was added sometimes with the addition of manure providing fiber for tensile strength as well as protein adhesive. Proteins in the manure act as binders. The hydrogen bonds of proteins must stay dry to remain strong, so the mud plaster must be kept dry. [12] With braced timber framed structures clay plaster was used on interior walls and ceilings as well as exterior walls as the wall cavity and exterior cladding isolated the clay plaster from moisture penetration. Application of clay plaster in brick structures risked water penetration from failed mortar joints on the exterior brick walls.In Economy Village, the rear and middle wythes of brick dwelling walls are laid in a clay and sand mortar with the front wythe bedded in a lime and sand mortar to provide a weather proof seal to protect from water penetration. This allowed a rendering of clay plaster and setting coat of thin lime and fine sand on exterior-walled rooms. Split lath was nailed with square cut lath nails, one into each framing member. With hand split lath the plasterer had the luxury of making lath to fit the cavity being plastered. Lengths of lath two to six foot are not uncommon at Economy Village.

Hand split lath is not uniform like sawn lath. The straightness or waviness of the grain affected the thickness or width of each lath, and thus the spacing of the lath.The clay plaster rough coat varied to cover the irregular lath. Window and door trim as well as the mudboard (baseboard) acted as screeds. With the variation of the lath thickness and use of coarse straw and manure, the clay coat of plaster was thick in comparison to later lime-only and gypsum plasters.

In Economy Village, the lime top coats are thin veneers often an eighth inch or less attesting to the scarcity of limestone supplies there. Clay plasters with their lack of tensile and compressive strength fell out of favor as industrial mining and technology advances in kiln production led to the exclusive use of lime and then gypsum in plaster applications. However, clay plasters still exist after hundreds of years clinging to split lath on rusty square nails. The wall variations and roughness reveal a hand-made and pleasing textured alternative to machine-made modern substrate finishes. But clay plaster finishes are rare and fleeting.According to Martin Weaver, Many of North Americas historic building interiorsare all too oftenone of the first things to disappear in the frenzy of demolition of interiors which has unfortunately come to be a common companion to heritage preservation in the guise of building rehabilitation. Gypsum plaster, or plaster of Paris, is produced by heating gypsum to about 300 °F (150 °C):[14]. CaSO4·2H2O + heat CaSO4·0.5H2O + 1.5H2O (released as steam). When the dry plaster powder is mixed with water, it re-forms into gypsum.

The setting of unmodified plaster starts about 10 minutes after mixing and is complete in about 45 minutes; but not fully set for 72 hours. [15] If plaster or gypsum is heated above 266 °F (130 °C), hemihydrate is formed, which will also re-form as gypsum if mixed with water. On heating to 180 °C, the nearly water-free form, called -anhydrite (CaSO4·nH2O where n = 0 to 0.05) is produced. Anhydrite reacts slowly with water to return to the dihydrate state, a property exploited in some commercial desiccants.

On heating above 250 °C, the completely anhydrous form called -anhydrite or dead burned plaster is formed. A large gypsum deposit at Montmartre in Paris led "calcined gypsum" (roasted gypsum or gypsum plaster) to be commonly known as "plaster of Paris".

Plasterers often use gypsum to simulate the appearance of surfaces of wood, stone, or metal, on movie and theatrical sets for example. Nowadays, theatrical plasterers often use expanded polystyrene, although the job title remains unchanged.

Plaster of Paris can be used to impregnate gauze bandages to make a sculpting material called plaster bandages. It is used similarly to clay, as it is easily shaped when wet, yet sets into a resilient and lightweight structure. This is the material that was (and sometimes still is) used to make classic plaster orthopedic casts to protect limbs with broken bones, the artistic use having been partly inspired by the medical use (see orthopedic cast). Set Modroc is an early example of a composite material. The hydration of plaster of Paris relies on the reaction of water with the dehydrated or partially hydrated calcium sulfate present in the plaster.Lime plaster is a mixture of calcium hydroxide and sand (or other inert fillers). Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere causes the plaster to set by transforming the calcium hydroxide into calcium carbonate (limestone). Whitewash is based on the same chemistry. To make lime plaster, limestone (calcium carbonate) is heated above approximately 850 °C to produce quicklime (calcium oxide).

Additional water is added to form a paste prior to use. The paste may be stored in airtight containers.When exposed to the atmosphere, the calcium hydroxide very slowly turns back into calcium carbonate through reaction with atmospheric carbon dioxide, causing the plaster to increase in strength. Lime plaster was a common building material for wall surfaces in a process known as lath and plaster, whereby a series of wooden strips on a studwork frame was covered with a semi-dry plaster that hardened into a surface. The plaster used in most lath and plaster construction was mainly lime plaster, with a cure time of about a month.

To stabilize the lime plaster during curing, small amounts of plaster of Paris were incorporated into the mix. Because plaster of Paris sets quickly, "retardants" were used to slow setting time enough to allow workers to mix large working quantities of lime putty plaster. A modern form of this method uses expanded metal mesh over wood or metal structures, which allows a great freedom of design as it is adaptable to both simple and compound curves. Today this building method has been partly replaced with drywall, also composed mostly of gypsum plaster.

In both these methods, a primary advantage of the material is that it is resistant to a fire within a room and so can assist in reducing or eliminating structural damage or destruction provided the fire is promptly extinguished. Lime plaster is used for frescoes, where pigments, diluted in water, are applied to the still wet plaster.

USA and Iran are the main plaster producers in the world. Cement plaster is a mixture of suitable plaster, sand, portland cement and water which is normally applied to masonry interiors and exteriors to achieve a smooth surface. Interior surfaces sometimes receive a final layer of gypsum plaster. Walls constructed with stock bricks are normally plastered while face brick walls are not plastered.Various cement-based plasters are also used as proprietary spray fireproofing products. These usually use vermiculite as lightweight aggregate. Heavy versions of such plasters are also in use for exterior fireproofing, to protect LPG vessels, pipe bridges and vessel skirts. The advantages of cement plaster noted at that time were its strength, hardness, quick setting time and durability.

Heat resistant plaster is a building material used for coating walls and chimney breasts and for use as a fire barrier in ceilings. Its purpose is to replace conventional gypsum plasters in cases where the temperature can get too high for gypsum plaster to stay on the wall or ceiling...

Main articles: Stucco and Plasterwork. Plaster may also be used to create complex detailing for use in room interiors. These may be geometric (simulating wood or stone) or naturalistic (simulating leaves, vines, and flowers).

These are also often used to simulate wood or stone detailing found in more substantial buildings. In modern days this material is also used for False Ceiling.

In this, the powder form is converted in a sheet form and the sheet is then attached to the basic ceiling with the help of fasteners. It is done in various designs containing various combinations of lights and colors. The common use of this plaster can be seen in the construction of houses. After the construction, direct painting is possible (the French do it), but elsewhere plaster is used. The walls are painted with the plaster which (in some countries) is nothing but calcium carbonate.

After drying the calcium carbonate plaster turns white and then the wall is ready to be painted. Elsewhere in the world, such as the UK, ever finer layers of plaster are added on top of the plasterboard (or sometimes the brick wall directly) to give a smooth brown polished texture ready for painting. Many of the greatest mural paintings in Europe, like Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, are executed in fresco, meaning they are painted on a thin layer of wet plaster, called intonaco; the pigments sink into this layer so that the plaster itself becomes the medium holding them, which accounts for the excellent durability of fresco. Additional work may be added a secco on top of the dry plaster, though this is generally less durable.Plaster (often called stucco in this context) is a far easier material for making reliefs than stone or wood, and was widely used for large interior wall-reliefs in Egypt and the Near East from antiquity into Islamic times (latterly for architectural decoration, as at the Alhambra), Rome, and Europe from at least the Renaissance, as well as probably elsewhere. However, it needs very good conditions to survive long in unmaintained buildings Roman decorative plasterwork is mainly known from Pompeii and other sites buried by ash from Mount Vesuvius. Plaster may be cast directly into a damp clay mold. In creating this piece molds (molds designed for making multiple copies) or waste molds (for single use) would be made of plaster. This "negative" image, if properly designed, may be used to produce clay productions, which when fired in a kiln become terra cotta building decorations, or these may be used to create cast concrete sculptures.

If a plaster positive was desired this would be constructed or cast to form a durable image artwork. As a model for stonecutters this would be sufficient. If intended for producing a bronze casting the plaster positive could be further worked to produce smooth surfaces. An advantage of this plaster image is that it is relatively cheap; should a patron approve of the durable image and be willing to bear further expense, subsequent molds could be made for the creation of a wax image to be used in lost wax casting, a far more expensive process. In lieu of producing a bronze image suitable for outdoor use the plaster image may be painted to resemble a metal image; such sculptures are suitable only for presentation in a weather-protected environment.Plaster expands while hardening then contracts slightly just before hardening completely. This makes plaster excellent for use in molds, and it is often used as an artistic material for casting. Plaster is also commonly spread over an armature (form), made of wire mesh, cloth, or other materials; a process for adding raised details. For these processes, limestone or acrylic based plaster may be employed, known as stucco.

Products composed mainly of plaster of Paris and a small amount of Portland cement are used for casting sculptures and other art objects as well as molds. Considerably harder and stronger than straight plaster of Paris, these products are for indoor use only as they rapidly degrade in the rain. The item "12 LIGHT UP PLASTER WITCH PUMPKIN STAND rare Halloween prop bowl stand garden" is in sale since Sunday, April 7, 2019. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Holiday & Seasonal\Props". The seller is "sidewaysstairsco" and is located in Santa Ana, California. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi arabia, Ukraine, United arab emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa rica, Dominican republic, Panama, Trinidad and tobago, Guatemala, El salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint kitts and nevis, Saint lucia, Montserrat, Turks and caicos islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman islands, Liechtenstein, Sri lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macao, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Viet nam, Uruguay, Russian federation.- Use Occasion: Halloween

- Theme: Halloween, witch, sorceress

- Country/Region of Manufacture: China

- Brand: Spooky Village