- Home

- Brand

- Disney (14)

- Distortions (45)

- Gemmy (430)

- Halloween (18)

- Handmade (30)

- Haunted Hill Farm (23)

- Home Accents Holiday (176)

- Magic Power (16)

- Morbid Enterprises (33)

- Morris (65)

- Morris Costumes (101)

- Seasonal Visions (155)

- Spirit (54)

- Spirit Halloween (210)

- Tekky (24)

- Tekky Toys (25)

- Trick Or Treat (16)

- Unknown (19)

- Www.horror-hall.com (24)

- Xcoser (85)

- ... (4662)

- Manufacturer

- Material

- Occasion

- Style

- Animated Prop (3)

- Anonymous (8)

- Armor (4)

- Classic (4)

- Complete Costume (3)

- Complete Outfit (7)

- Cosplay (31)

- Cosplay Helmet (2)

- Decorations & Props (42)

- Full Head Helmet (12)

- Full Head Mask (4)

- Full Mask (9)

- Helmet (3)

- Helmet Mask (4)

- Mask (8)

- Mask, Helmet (3)

- Prop (18)

- Props (3)

- See Description (4)

- Suit (3)

- ... (6050)

- Theme

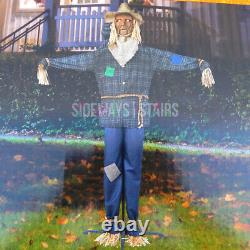

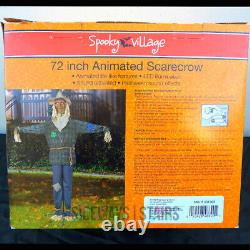

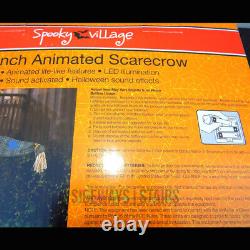

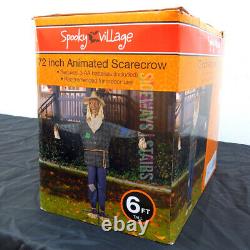

72 TALKING SCARECROW HALLOWEEN PROP decoration light sound animated creepy crow

Check out our other new and used Halloween-themed items>>>>> HERE! An awesomely creepy Halloween decoration that talks and lights up. 72 ANIMATED SCARECROW HALLOWEEN PROP BY SPOOKY VILLAGE. Sure to spook and delight! This nifty 6' animated Halloween prop features a classic style scarecrow that talks and of course a creepy black crow.

The scarecrow is dressed in a green plaid button-up shirt, blue pants, straw style hat, and has hay hands, feet, and hair. When activated, either by the "TRY ME" button at the wrist or by sound, both the crow's and scarecrow's eyes glow a demon red color and the scarecrow begins to speak. The scarecrow's jaw moves while he says one of the following: Hey, get off my lawn! ", "You don't know a scarecrow when you see one?

", "Looks we have some trespassers, get out of here! The crow makes sound and the scarecrow laughs as well.

Ideal for displaying during the Halloween season though lovers of everything macabre can enjoy it all-year-round as it sits in a corner of their decorated room (mancave) or house of horrors. This is the perfect prop for your porch (covered porch recommended). Complete with box and instructions. Because the box is not taped shut we assume this was used for a short period as a store display. Box has a fair amount of storage wear (some not shown). ALL PHOTOS AND TEXT ARE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OF SIDEWAYS STAIRS CO. Halloween or Hallowe'en (a contraction of Hallows' Even or Hallows' Evening), [5] also known as Allhalloween, [6] All Hallows' Eve, [7] or All Saints' Eve, [8] is a celebration observed in several countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day. It begins the three-day observance of Allhallowtide, [9] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed. It is widely believed that many Halloween traditions originated from ancient Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain; that such festivals may have had pagan roots; and that Samhain itself was Christianized as Halloween by the early Church.[12][13][14][15][16] Some believe, however, that Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, separate from ancient festivals like Samhain. Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising and souling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins into jack-o'-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, as well as watching horror films. [21] In many parts of the world, the Christian religious observances of All Hallows' Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead, remain popular, [22][23][24] although elsewhere it is a more commercial and secular celebration. [25][26][27] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows' Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes...

The word Halloween or Hallowe'en dates to about 1745[32] and is of Christian origin. [33] The word "Hallowe'en" means "Saints' evening". [34] It comes from a Scottish term for All Hallows' Eve (the evening before All Hallows' Day). [35] In Scots, the word "eve" is even, and this is contracted to e'en or een.

Over time, (All) Hallow(s) E(v)en evolved into Hallowe'en. Although the phrase "All Hallows'" is found in Old English "All Hallows' Eve" is itself not seen until 1556.... [38] Historian Nicholas Rogers, exploring the origins of Halloween, notes that while some folklorists have detected its origins in the Roman feast of Pomona, the goddess of fruits and seeds, or in the festival of the dead called Parentalia, it is more typically linked to the Celtic festival of Samhain, which comes from the Old Irish for'summer's end'. Samhain (/swn, san/) was the first and most important of the four quarter days in the medieval Gaelic calendar and was celebrated on 31 October 1 November[citation needed] in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.

[40][41] A kindred festival was held at the same time of year by the Brittonic Celts, called Calan Gaeaf in Wales, Kalan Gwav in Cornwall and Kalan Goañv in Brittany; a name meaning "first day of winter". For the Celts, the day ended and began at sunset; thus the festival began on the evening before 7 November by modern reckoning (the half point between equinox and solstice). [42] Samhain and Calan Gaeaf are mentioned in some of the earliest Irish and Welsh literature. Samhain/Calan Gaeaf marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the'darker half' of the year. [44][45] Like Beltane/Calan Mai, it was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí (Connacht pronunciation /isi/ eess-SHEE, Munster /e:s i:/), the'spirits' or'fairies', could more easily come into this world and were particularly active.[46][47] Most scholars see the Aos Sí as degraded versions of ancient gods... Whose power remained active in the people's minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs. [48] The Aos Sí were both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings.

[49][50] At Samhain, it was believed that the Aos Sí needed to be propitiated to ensure that the people and their livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for the Aos Sí. [51][52][53] The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality. [54] Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.[55] The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures throughout the world. [56] In 19th century Ireland, candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin. Throughout Ireland and Britain, the household festivities included rituals and games intended to foretell one's future, especially regarding death and marriage. [58] Apples and nuts were often used in these divination rituals.

They included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others. [59] Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers, and were also used for divination. [44] In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them.[43] It is suggested that the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic they mimicked the Sun, helping the "powers of growth" and holding back the decay and darkness of winter. [55][60][61] In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes. [62] In Wales, bonfires were lit to "prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth". [63] Later, these bonfires served to keep "away the devil". From at least the 16th century, [65] the festival included mumming and guising in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Wales.

It may have originally been a tradition whereby people impersonated the Aos Sí, or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf, similar to the custom of souling (see below). Impersonating these beings, or wearing a disguise, was also believed to protect oneself from them. [68] In parts of southern Ireland, the guisers included a hobby horse.

If the household donated food it could expect good fortune from the'Muck Olla'; not doing so would bring misfortune. [69] In Scotland, youths went house-to-house with masked, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed.

Marian McNeill suggests the ancient festival included people in costume representing the spirits, and that faces were marked (or blackened) with ashes taken from the sacred bonfire. [65] In parts of Wales, men went about dressed as fearsome beings called gwrachod. [66] In the late 19th and early 20th century, young people in Glamorgan and Orkney cross-dressed. Elsewhere in Europe, mumming and hobby horses were part of other yearly festivals. However, in the Celtic-speaking regions they were "particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers".

[66] From at least the 18th century, "imitating malignant spirits" led to playing pranks in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. Wearing costumes and playing pranks at Halloween spread to England in the 20th century. [66] Traditionally, pranksters used hollowed out turnips or mangel wurzels often carved with grotesque faces as lanterns. [66] By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits, [66] or were used to ward off evil spirits.

[70][71] They were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century, [66] as well as in Somerset (see Punkie Night). In the 20th century they spread to other parts of England and became generally known as jack-o'-lanterns. [72] Halloween is the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows' Day (also known as All Saints' or Hallowmas) on 1 November and All Souls' Day on 2 November, thus giving the holiday on 31 October the full name of All Hallows' Eve (meaning the evening before All Hallows' Day). [73] Since the time of the early Church, [74] major feasts in Christianity (such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost) had vigils that began the night before, as did the feast of All Hallows'. [75] These three days are collectively called Allhallowtide and are a time for honoring the saints and praying for the recently departed souls who have yet to reach Heaven.Commemorations of all saints and martyrs were held by several churches on various dates, mostly in springtime. [76] In 609, Pope Boniface IV re-dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to "St Mary and all martyrs" on 13 May.

This was the same date as Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival of the dead, and the same date as the commemoration of all saints in Edessa in the time of Ephrem. The feast of All Hallows', on its current date in the Western Church, may be traced to Pope Gregory III's (731741) founding of an oratory in St Peter's for the relics "of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors". [78][79] In 835, All Hallows' Day was officially switched to 1 November, the same date as Samhain, at the behest of Pope Gregory IV. [80] Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea, [80] although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter.

[81] They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of'dying' in nature. [80][81] It is also suggested that the change was made on the "practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it", and perhaps because of public health considerations regarding Roman Fever a disease that claimed a number of lives during the sultry summers of the region. By the end of the 12th century they had become holy days of obligation across Europe and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for the souls in purgatory.

In addition, it was customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls. "[84] "Souling, the custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls, [85] has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating. [86] The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century[87] and was found in parts of England, Flanders, Germany and Austria. [87][88][89] Soul cakes would also be offered for the souls themselves to eat, [56] or the'soulers' would act as their representatives.

[90] As with the Lenten tradition of hot cross buns, Allhallowtide soul cakes were often marked with a cross, indicating that they were baked as alms. [91] Shakespeare mentions souling in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593). [92] On the custom of wearing costumes, Christian minister Prince Sorie Conteh wrote: It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints' Day, and All Hallows' Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes to disguise their identities. It is claimed that in the Middle Ages, churches that were too poor to display the relics of martyred saints at Allhallowtide let parishioners dress up as saints instead.[94][95] Some Christians continue to observe this custom at Halloween today. [96] Lesley Bannatyne believes this could have been a Christianization of an earlier pagan custom. [97] While souling, Christians would carry with them "lanterns made of hollowed-out turnips". [98] It has been suggested that the carved jack-o'-lantern, a popular symbol of Halloween, originally represented the souls of the dead.

[99] On Halloween, in medieval Europe, fires served a dual purpose, being lit to guide returning souls to the homes of their families, as well as to deflect demons from haunting sincere Christian folk. [100][101] Households in Austria, England and Ireland often had "candles burning in every room to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes". These were known as "soul lights". [102][103][104] Many Christians in mainland Europe, especially in France, believed "that once a year, on Hallowe'en, the dead of the churchyards rose for one wild, hideous carnival" known as the danse macabre, which has often been depicted in church decoration. [105] Christopher Allmand and Rosamond McKitterick write in The New Cambridge Medieval History that Christians were moved by the sight of the Infant Jesus playing on his mother's knee; their hearts were touched by the Pietà; and patron saints reassured them by their presence.

But, all the while, the danse macabre urged them not to forget the end of all earthly things. "[106] This danse macabre was enacted at village pageants and at court masques, with people "dressing up as corpses from various strata of society, and may have been the origin of modern-day Halloween costume parties.Thus, for some Nonconformist Protestants, the theology of All Hallows' Eve was redefined; without the doctrine of purgatory, the returning souls cannot be journeying from Purgatory on their way to Heaven, as Catholics frequently believe and assert. Instead, the so-called ghosts are thought to be in actuality evil spirits. As such they are threatening. [73][110] Mark Donnelly, a professor of medieval archaeology, and historian Daniel Diehl, with regard to the evil spirits, on Halloween, write that barns and homes were blessed to protect people and livestock from the effect of witches, who were believed to accompany the malignant spirits as they traveled the earth.

[111] In the 19th century, in some rural parts of England, families gathered on hills on the night of All Hallows' Eve. One held a bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the rest knelt around him in a circle, praying for the souls of relatives and friends until the flames went out. This was known as teen'lay. [113] The rising popularity of Guy Fawkes Night (5 November) from 1605 onward, saw many Halloween traditions appropriated by that holiday instead, and Halloween's popularity waned in Britain, with the noteworthy exception of Scotland. [114] There and in Ireland, they had been celebrating Samhain and Halloween since at least the early Middle Ages, and the Scottish kirk took a more pragmatic approach to Halloween, seeing it as important to the life cycle and rites of passage of communities and thus ensuring its survival in the country.

In France, some Christian families, on the night of All Hallows' Eve, prayed beside the graves of their loved ones, setting down dishes full of milk for them. [102] On Halloween, in Italy, some families left a large meal out for ghosts of their passed relatives, before they departed for church services. [115] In Spain, on this night, special pastries are baked, known as "bones of the holy" (Spanish: Huesos de Santo) and put them on the graves of the churchyard, a practice that continues to this day... Lesley Bannatyne and Cindy Ott both write that Anglican colonists in the southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland "recognized All Hallow's Eve in their church calendars", [117][118] although the Puritans of New England maintained strong opposition to the holiday, along with other traditional celebrations of the established Church, including Christmas.[119] Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century give no indication that Halloween was widely celebrated in North America. [120] It was not until mass Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century that Halloween became a major holiday in North America.

[120] Confined to the immigrant communities during the mid-19th century, it was gradually assimilated into mainstream society and by the first decade of the 20th century it was being celebrated coast to coast by people of all social, racial and religious backgrounds. [121] In Cajun areas, a nocturnal Mass was said in cemeteries on Halloween night. Candles that had been blessed were placed on graves, and families sometimes spent the entire night at the graveside.

[122] The yearly New York Halloween Parade, begun in 1974 by puppeteer and mask maker Ralph Lee of Greenwich Village, is the world's largest Halloween parade and America's only major nighttime parade, attracting more than 60,000 costumed participants, two million spectators, and a worldwide television audience of over 100 million... Development of artifacts and symbols associated with Halloween formed over time.Jack-o'-lanterns are traditionally carried by guisers on All Hallows' Eve in order to frighten evil spirits. [99][124] There is a popular Irish Christian folktale associated with the jack-o'-lantern, [125] which in folklore is said to represent a "soul who has been denied entry into both heaven and hell":[126]. On route home after a night's drinking, Jack encounters the Devil and tricks him into climbing a tree.

A quick-thinking Jack etches the sign of the cross into the bark, thus trapping the Devil. Jack strikes a bargain that Satan can never claim his soul. After a life of sin, drink, and mendacity, Jack is refused entry to heaven when he dies. Keeping his promise, the Devil refuses to let Jack into hell and throws a live coal straight from the fires of hell at him. It was a cold night, so Jack places the coal in a hollowed out turnip to stop it from going out, since which time Jack and his lantern have been roaming looking for a place to rest.In Ireland and Scotland, the turnip has traditionally been carved during Halloween, [128][129] but immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin, which is both much softer and much larger making it easier to carve than a turnip. [128] The American tradition of carving pumpkins is recorded in 1837[130] and was originally associated with harvest time in general, not becoming specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late 19th century. [132][133] Imagery of the skull, a reference to Golgotha in the Christian tradition, serves as "a reminder of death and the transitory quality of human life" and is consequently found in memento mori and vanitas compositions;[134] skulls have therefore been commonplace in Halloween, which touches on this theme. [135] Traditionally, the back walls of churches are "decorated with a depiction of the Last Judgment, complete with graves opening and the dead rising, with a heaven filled with angels and a hell filled with devils", a motif that has permeated the observance of this triduum.

[136] One of the earliest works on the subject of Halloween is from Scottish poet John Mayne, who, in 1780, made note of pranks at Halloween; What fearfu' pranks ensue! ", as well as the supernatural associated with the night, "Bogies" (ghosts), influencing Robert Burns' "Halloween (1785). [137] Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent. Homes are often decorated with these types of symbols around Halloween. Halloween imagery includes themes of death, evil, and mythical monsters. [138] Black, orange, and sometimes purple are Halloween's traditional colors... Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween. " The word "trick" implies a "threat to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given. [86] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling. [139] John Pymm writes that many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church. [140] These feast days included All Hallows' Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday. [141][142] Mumming practiced in Germany, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, [143] involved masked persons in fancy dress who "paraded the streets and entered houses to dance or play dice in silence". [88] In the Philippines, the practice of souling is called Pangangaluwa and is practiced on All Hallow's Eve among children in rural areas.[21] People drape themselves in white cloths to represent souls and then visit houses, where they sing in return for prayers and sweets. [129][147] The practice of guising at Halloween in North America is first recorded in 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, Canada reported children going "guising" around the neighborhood. American historian and author Ruth Edna Kelley of Massachusetts wrote the first book-length history of Halloween in the US; The Book of Hallowe'en (1919), and references souling in the chapter "Hallowe'en in America". While the first reference to "guising" in North America occurs in 1911, another reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920. [151] The earliest known use in print of the term "trick or treat" appears in 1927, in the Blackie Herald Alberta, Canada.

The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show children but not trick-or-treating. [153] Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice until the 1930s, with the first US appearances of the term in 1934, [154] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.

A popular variant of trick-or-treating, known as trunk-or-treating (or Halloween tailgaiting), occurs when "children are offered treats from the trunks of cars parked in a church parking lot", or sometimes, a school parking lot. [116][156] In a trunk-or-treat event, the trunk (boot) of each automobile is decorated with a certain theme, [157] such as those of children's literature, movies, scripture, and job roles.

[158] Trunk-or-treating has grown in popularity due to its perception as being more safe than going door to door, a point that resonates well with parents, as well as the fact that it "solves the rural conundrum in which homes [are] built a half-mile apart"... Halloween costumes are traditionally modeled after supernatural figures such as vampires, monsters, ghosts, skeletons, witches, and devils. Over time, in the United States, the costume selection extended to include popular characters from fiction, celebrities, and generic archetypes such as ninjas and princesses.

Dressing up in costumes and going "guising" was prevalent in Scotland and Ireland at Halloween by the late 19th century. [129] A Scottish term, the tradition is called "guising" because of the disguises or costumes worn by the children. [147] In Ireland the masks are known as'false faces'. [161] Costuming became popular for Halloween parties in the US in the early 20th century, as often for adults as for children. The first mass-produced Halloween costumes appeared in stores in the 1930s when trick-or-treating was becoming popular in the United States.Smith, in his book Halloween, Hallowed is Thy Name, offers a religious perspective to the wearing of costumes on All Hallows' Eve, suggesting that by dressing up as creatures "who at one time caused us to fear and tremble", people are able to poke fun at Satan "whose kingdom has been plundered by our Saviour". Images of skeletons and the dead are traditional decorations used as memento mori.

"Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF" is a fundraising program to support UNICEF, [86] a United Nations Programme that provides humanitarian aid to children in developing countries. Started as a local event in a Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood in 1950 and expanded nationally in 1952, the program involves the distribution of small boxes by schools (or in modern times, corporate sponsors like Hallmark, at their licensed stores) to trick-or-treaters, in which they can solicit small-change donations from the houses they visit. In Canada, in 2006, UNICEF decided to discontinue their Halloween collection boxes, citing safety and administrative concerns; after consultation with schools, they instead redesigned the program...

The most popular costumes for pets are the pumpkin, followed by the hot dog, and the bumble bee in third place... There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween. Some of these games originated as divination rituals or ways of foretelling one's future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a "rare few" in rural communities as they were considered to be "deadly serious" practices.[167] In recent centuries, these divination games have been "a common feature of the household festivities" in Ireland and Britain. [58] They often involve apples and hazelnuts.

In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom. [168] Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona. The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th20th centuries. Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today. One common game is apple bobbing or dunking (which may be called "dooking" in Scotland)[169] in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water and the participants must use only their teeth to remove an apple from the basin.

A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drive the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a sticky face.Another once-popular game involves hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other. The rod is spun round and everyone takes turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth. Several of the traditional activities from Ireland and Britain involve foretelling one's future partner or spouse.

An apple would be peeled in one long strip, then the peel tossed over the shoulder. The peel is believed to land in the shape of the first letter of the future spouse's name. [171][172] Two hazelnuts would be roasted near a fire; one named for the person roasting them and the other for the person they desire.

If the nuts jump away from the heat, it is a bad sign, but if the nuts roast quietly it foretells a good match. [173][174] A salty oatmeal bannock would be baked; the person would eat it in three bites and then go to bed in silence without anything to drink. This is said to result in a dream in which their future spouse offers them a drink to quench their thirst.[175] Unmarried women were told that if they sat in a darkened room and gazed into a mirror on Halloween night, the face of their future husband would appear in the mirror. [176] However, if they were destined to die before marriage, a skull would appear.

The custom was widespread enough to be commemorated on greeting cards[177] from the late 19th century and early 20th century. In Ireland and Scotland, items would be hidden in food usually a cake, barmbrack, cranachan, champ or colcannon and portions of it served out at random. A person's future would be foretold by the item they happened to find; for example, a ring meant marriage and a coin meant wealth.

Up until the 19th century, the Halloween bonfires were also used for divination in parts of Scotland, Wales and Brittany. When the fire died down, a ring of stones would be laid in the ashes, one for each person.

In the morning, if any stone was mislaid it was said that the person it represented would not live out the year. Telling ghost stories and watching horror films are common fixtures of Halloween parties. Episodes of television series and Halloween-themed specials (with the specials usually aimed at children) are commonly aired on or before Halloween, while new horror films are often released before Halloween to take advantage of the holiday...Haunted attractions are entertainment venues designed to thrill and scare patrons. Most attractions are seasonal Halloween businesses that may include haunted houses, corn mazes, and hayrides, [179] and the level of sophistication of the effects has risen as the industry has grown.

The first recorded purpose-built haunted attraction was the Orton and Spooner Ghost House, which opened in 1915 in Liphook, England. This attraction actually most closely resembles a carnival fun house, powered by steam.

[180][181] The House still exists, in the Hollycombe Steam Collection. It was during the 1930s, about the same time as trick-or-treating, that Halloween-themed haunted houses first began to appear in America. It was in the late 1950s that haunted houses as a major attraction began to appear, focusing first on California. Sponsored by the Children's Health Home Junior Auxiliary, the San Mateo Haunted House opened in 1957. The San Bernardino Assistance League Haunted House opened in 1958.

Home haunts began appearing across the country during 1962 and 1963. In 1964, the San Manteo Haunted House opened, as well as the Children's Museum Haunted House in Indianapolis. The haunted house as an American cultural icon can be attributed to the opening of the Haunted Mansion in Disneyland on 12 August 1969.

[183] Knott's Berry Farm began hosting its own Halloween night attraction, Knott's Scary Farm, which opened in 1973. [184] Evangelical Christians adopted a form of these attractions by opening one of the first "hell houses" in 1972.

The first Halloween haunted house run by a nonprofit organization was produced in 1970 by the Sycamore-Deer Park Jaycees in Clifton, Ohio. It was last produced in 1982. [186] Other Jaycees followed suit with their own versions after the success of the Ohio house.

The March of Dimes copyrighted a "Mini haunted house for the March of Dimes" in 1976 and began fundraising through their local chapters by conducting haunted houses soon after. Although they apparently quit supporting this type of event nationally sometime in the 1980s, some March of Dimes haunted houses have persisted until today. On the evening of 11 May 1984, in Jackson Township, New Jersey, the Haunted Castle (Six Flags Great Adventure) caught fire. As a result of the fire, eight teenagers perished.

[188] The backlash to the tragedy was a tightening of regulations relating to safety, building codes and the frequency of inspections of attractions nationwide. The smaller venues, especially the nonprofit attractions, were unable to compete financially, and the better funded commercial enterprises filled the vacuum. [189][190] Facilities that were once able to avoid regulation because they were considered to be temporary installations now had to adhere to the stricter codes required of permanent attractions.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, theme parks entered the business seriously. Six Flags Fright Fest began in 1986 and Universal Studios Florida began Halloween Horror Nights in 1991. Knott's Scary Farm experienced a surge in attendance in the 1990s as a result of America's obsession with Halloween as a cultural event.

Theme parks have played a major role in globalizing the holiday. Universal Studios Singapore and Universal Studios Japan both participate, while Disney now mounts Mickey's Not-So-Scary Halloween Party events at its parks in Paris, Hong Kong and Tokyo, as well as in the United States. [194] The theme park haunts are by far the largest, both in scale and attendance... On All Hallows' Eve, many Western Christian denominations encourage abstinence from meat, giving rise to a variety of vegetarian foods associated with this day.Because in the Northern Hemisphere Halloween comes in the wake of the yearly apple harvest, candy apples (known as toffee apples outside North America), caramel apples or taffy apples are common Halloween treats made by rolling whole apples in a sticky sugar syrup, sometimes followed by rolling them in nuts. At one time, candy apples were commonly given to trick-or-treating children, but the practice rapidly waned in the wake of widespread rumors that some individuals were embedding items like pins and razor blades in the apples in the United States.

[197] While there is evidence of such incidents, [198] relative to the degree of reporting of such cases, actual cases involving malicious acts are extremely rare and have never resulted in serious injury. Nonetheless, many parents assumed that such heinous practices were rampant because of the mass media. At the peak of the hysteria, some hospitals offered free X-rays of children's Halloween hauls in order to find evidence of tampering. Virtually all of the few known candy poisoning incidents involved parents who poisoned their own children's candy. [200] It is considered fortunate to be the lucky one who finds it.[200] It has also been said that those who get a ring will find their true love in the ensuing year. This is similar to the tradition of king cake at the festival of Epiphany. List of foods associated with Halloween. Candy apples/toffee apples (Great Britain and Ireland). Candy apples, candy corn, candy pumpkins (North America).

Monkey nuts (peanuts in their shells) (Ireland and Scotland). Novelty candy shaped like skulls, pumpkins, bats, worms, etc.

On Hallowe'en (All Hallows' Eve), in Poland, believers were once taught to pray out loud as they walk through the forests in order that the souls of the dead might find comfort; in Spain, Christian priests in tiny villages toll their church bells in order to remind their congregants to remember the dead on All Hallows' Eve. [201] In Ireland, and among immigrants in Canada, a custom includes the Christian practice of abstinence, keeping All Hallows' Eve as a meat-free day, and serving pancakes or colcannon instead. [202] In Mexico children make an altar to invite the return of the spirits of dead children (angelitos). The Christian Church traditionally observed Hallowe'en through a vigil. Worshippers prepared themselves for feasting on the following All Saints' Day with prayers and fasting.

[204] This church service is known as the Vigil of All Hallows or the Vigil of All Saints;[205][206] an initiative known as Night of Light seeks to further spread the Vigil of All Hallows throughout Christendom. [207][208] After the service, "suitable festivities and entertainments" often follow, as well as a visit to the graveyard or cemetery, where flowers and candles are often placed in preparation for All Hallows' Day. [209][210] In Finland, because so many people visit the cemeteries on All Hallows' Eve to light votive candles there, they "are known as valomeri, or seas of light".

Today, Christian attitudes towards Halloween are diverse. In the Anglican Church, some dioceses have chosen to emphasize the Christian traditions associated with All Hallow's Eve. [212][213] Some of these practices include praying, fasting and attending worship services. O LORD our God, increase, we pray thee, and multiply upon us the gifts of thy grace: that we, who do prevent the glorious festival of all thy Saints, may of thee be enabled joyfully to follow them in all virtuous and godly living. Through Jesus Christ, Our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end.

Collect of the Vigil of All Saints, The Anglican Breviary[214]. Other Protestant Christians also celebrate All Hallows' Eve as Reformation Day, a day to remember the Protestant Reformation, alongside All Hallow's Eve or independently from it.

[215][216] This is because Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-five Theses to All Saints' Church in Wittenberg on All Hallows' Eve. [217] Often, "Harvest Festivals" or "Reformation Festivals" are held on All Hallows' Eve, in which children dress up as Bible characters or Reformers. [218] In addition to distributing candy to children who are trick-or-treating on Hallowe'en, many Christians also provide gospel tracts to them.

One organization, the American Tract Society, stated that around 3 million gospel tracts are ordered from them alone for Hallowe'en celebrations. [219] Others order Halloween-themed Scripture Candy to pass out to children on this day.

Some Christians feel concerned about the modern celebration of Halloween because they feel it trivializes or celebrates paganism, the occult, or other practices and cultural phenomena deemed incompatible with their beliefs. [222] Father Gabriele Amorth, an exorcist in Rome, has said, if English and American children like to dress up as witches and devils on one night of the year that is not a problem. If it is just a game, there is no harm in that. "[223] In more recent years, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston has organized a "Saint Fest on Halloween. [224] Similarly, many contemporary Protestant churches view Halloween as a fun event for children, holding events in their churches where children and their parents can dress up, play games, and get candy for free.To these Christians, Halloween holds no threat to the spiritual lives of children: being taught about death and mortality, and the ways of the Celtic ancestors actually being a valuable life lesson and a part of many of their parishioners' heritage. [225] Christian minister Sam Portaro wrote that Halloween is about using "humor and ridicule to confront the power of death". In the Roman Catholic Church, Halloween's Christian connection is acknowledged, and Halloween celebrations are common in many Catholic parochial schools. [227][228] Many fundamentalist and evangelical churches use "Hell houses" and comic-style tracts in order to make use of Halloween's popularity as an opportunity for evangelism.

[229] Others consider Halloween to be completely incompatible with the Christian faith due to its putative origins in the Festival of the Dead celebration. [230] Indeed, even though Eastern Orthodox Christians observe All Hallows' Day on the First Sunday after Pentecost, The Eastern Orthodox Church recommends the observance of Vespers or a Paraklesis on the Western observance of All Hallows' Eve, out of the pastoral need to provide an alternative to popular celebrations...The traditions and importance of Halloween vary greatly among countries that observe it. [244][245] In Brittany children would play practical jokes by setting candles inside skulls in graveyards to frighten visitors.

[246] Mass transatlantic immigration in the 19th century popularized Halloween in North America, and celebration in the United States and Canada has had a significant impact on how the event is observed in other nations. This larger North American influence, particularly in iconic and commercial elements, has extended to places such as Ecuador, Chile, [247] Australia, [248] New Zealand, [249] (most) continental Europe, Japan, and other parts of East Asia.[252] In Mexico and Latin America in general, it is referred to as " Día de Muertos " which translates in English to "Day of the dead". Most of the people from Latin America construct altars in their homes to honor their deceased relatives and they decorate them with flowers and candies and other offerings. A scarecrow is a decoy or mannequin, often in the shape of a human. Humanoid scarecrows are usually dressed in old clothes and placed in open fields to discourage birds from disturbing and feeding on recently cast seed and growing crops. [1] Scarecrows are used across the world by farmers, and are a notable symbol of farms and the countryside in popular culture...

The common form of a scarecrow is a humanoid figure dressed in old clothes and placed in open fields to discourage birds such as crows or sparrows from disturbing and feeding on recently cast seed and growing crops. [1] Machinery such as windmills have been employed as scarecrows, but the effectiveness lessens as animals become familiar with the structures. Since the creation of the humanoid scarecrow, more effective methods have been developed. On California farmland, highly reflective aluminized PET film ribbons are tied to the plants to create shimmers from the sun. Another approach is using automatic noise guns powered by propane gas.

One winery in New York uses inflatable tube men or airdancers to scare away birds... In Kojiki, the oldest surviving book in Japan (compiled in the year 712), a scarecrow known as Kuebiko appears as a deity who cannot walk, yet knows everything about the world. Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story "Feathertop" is about a scarecrow created and brought to life in 17th century Salem, Massachusetts by a witch in league with the devil.

The basic framework of the story was used by American dramatist Percy MacKaye in his 1908 play The Scarecrow. Frank Baum's tale The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has a scarecrow as one of the main protagonists. The Scarecrow of Oz was searching for brains from the Great Wizard. The scarecrow was portrayed by Frank Moore in the 1914 film His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz, by Ray Bolger in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, and by Michael Jackson in the 1978 musical film adaptation The Wiz.

Worzel Gummidge, a scarecrow who came to life in a friendly form, first appeared in series of novels by Barbara Euphan Todd in the 1930s and later in a popular television adaptation. The Scarecrow is the alter ego of the Reverend Doctor Christopher Syn, the smuggler hero in a series of novels written by Russell Thorndike. The story was made into the movie Doctor Syn in 1937, and again in 1962 as Captain Clegg. It was taken up by Disney in 1963 and dramatized in the three-part TV miniseries The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh starring Patrick McGoohan; this was later re-edited and released theatrically as Dr. A film directed by Jerry Schatzberg in 1973 starring Al Pacino and Gene Hackman is titled Scarecrow and deals with two characters on a journey reminiscent of the one in L.

The Scarecrow is a character in the DC Comics universe, a supervillain and antagonist of Batman; Cillian Murphy portrays the character in Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy. Similar characters, known as Scarecrow and Straw Man, have appeared in Marvel Comics.

British band Pink Floyd recorded a song called "The Scarecrow" for their debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. John Cougar Mellencamp's album Scarecrow, which peaked at No.

2 in 1985, spawned five Top 40 singles including "Rain on the Scarecrow" (#21). The song "Scarecrow People" on the XTC album Oranges & Lemons is a cautionary tale about the evolution of mankind to'scarecrow people' who'ain't got no brains' and'ain't got no hearts' and are the result of humans destroying their world with wars and pollution. Melissa Etheridge recorded the song "Scarecrow" for her 1999 album Breakdown. The song is actually about Matthew Shepard.

The title makes reference to the bicyclist who found Shepard murdered and tied to a fence, and mistook him as a scarecrow upon first glance. Tobias Sammet recorded his third Avantasia album with a title The Scarecrow, as a first part of Wicked Trilogy.

A scarecrow named Scarecrow is one of the protagonists in Magic Adventures of Mumfie. Joe's Scarecrow Village in Cape Breton, Canada is a roadside attraction displaying dozens of scarecrows. The Japanese village of Nagoro, on the island of Shikoku in the Tokushima Prefecture, has 35 inhabitants but more than 350 scarecrows... In England , the Urchfont Scarecrow Festival [6] was established in the 1990s and has grown into a major local event, attracting up to 10,000 people annually for the May Day Bank Holiday. Originally based on an idea imported from Derbyshire, it was the first Scarecrow Festival to be established in the whole of southern England.[7][8] The village of Meerbrook in Staffordshire holds an annual Scarecrow Festival during the month of May. Tetford and Salmonby, Lincolnshire jointly host one. The festival at Wray, Lancashire was established in the early 1990s and continues to the present day. In the village of Orton, Eden, Cumbria scarecrows are displayed each year, often using topical themes such as a Dalek exterminating a Wind turbine to represent local opposition to a wind farm.

The village of Blackrod, near Bolton in Greater Manchester, holds a popular annual Scarecrow Festival over a weekend usually in early July. Norland, West Yorkshire has a Scarecrow festival. Kettlewell in North Yorkshire has held an annual festival since 1994. [9] In Teesdale, County Durham, the villages of Cotherstone, Staindrop and Middleton-in-Teesdale have annual scarecrow festivals.Scotland's first scarecrow festival was held in West Kilbride, North Ayrshire in 2004, [10] and there is also one held in Montrose. On the Isle of Skye, the Tattie bogal event[11] is held each year, featuring a scarecrow trail and other events. Gisburn, Lancashire held its first Scarecrow Festival in June 2014.

Mullion, in Cornwall, has an annual scarecrow festival since 2007. Charles, Illinois hosts an annual Scarecrow Festival. [13] Peddler's Village in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, hosts an annual scarecrow festival and presents a scarecrow display in September-October that draws tens of thousands of visitors. The'pumpkin people' come in the fall months in the valley region of Nova Scotia, Canada. They are scarecrows with pumpkin heads doing various things such as playing the fiddle or riding a wooden horse.

Hickling, in the south of Nottinghamshire, is another village that celebrates an annual scarecrow event. [14] Meaford, Ontario has celebrated the Scarecrow Invasion since 1996. In the Philippines, the Province of Isabela has recently started a scarecrow festival named after the local language: the Bambanti Festival. The Province invites all its Cities and Towns to participate for the festivities, that lasts a week, and has drawn tourists from around the island of Luzon. The largest gathering of scarecrows in one location is 3,812 and was achieved by National Forest Adventure Farm (UK) in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, UK, on 7 August 2014. Bird scarers are a number of devices designed to scare birds, usually employed by farmers to dissuade birds from eating recently planted arable crops. They are also used on airfields to prevent birds accumulating near runways and causing a potential hazard to aircraft... One of the oldest designs of bird scarer is the scarecrow which is in the shape of a human figure.The scarecrow idea has been built upon numerous times, and not all visual scare devices are shaped like humans. The "Flashman Birdscarer, " Iridescent tape, "TerrorEyes" balloons, and other visual deterrents are all built on the idea of visually scaring birds. This method doesn't work so well with all species, considering that some species frequently perch on scarecrows. The item "72 TALKING SCARECROW HALLOWEEN PROP decoration light sound animated creepy crow" is in sale since Monday, October 21, 2019.

This item is in the category "Collectibles\Holiday & Seasonal\Props". The seller is "sidewaysstairsco" and is located in Santa Ana, California. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi arabia, Ukraine, United arab emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa rica, Dominican republic, Panama, Trinidad and tobago, Guatemala, El salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint kitts and nevis, Saint lucia, Montserrat, Turks and caicos islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman islands, Liechtenstein, Sri lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macao, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Viet nam, Uruguay, Russian federation.

- Country/Region of Manufacture: China

- Brand: Spooky Village